Smartphone app to support goal setting in pediatric rehabilitation: app development, usability and acceptability study | Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation

Phase 1: application development

This phase aimed to create a prototype that considered current scientific evidence.

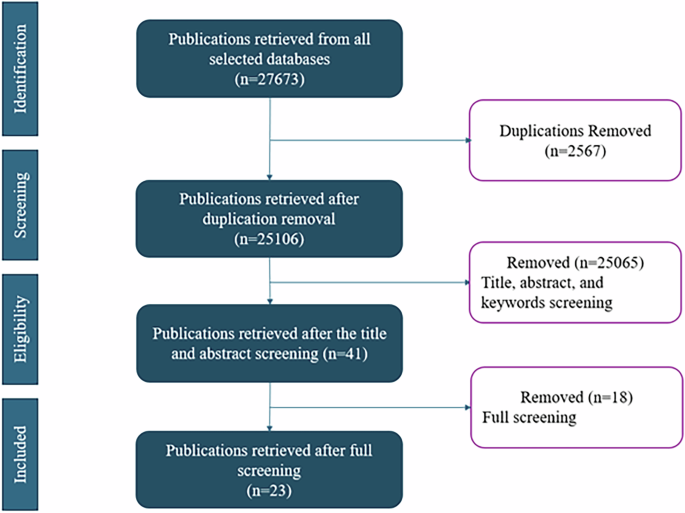

Literature review

The literature review highlighted the following key elements of the goal-setting process, which were used to inform the development of the “Kid’EM-app”. It is essential for the professional to get to know the child by asking them about the things they enjoy and their needs so that their everyday difficulties emerge [41]. Children are able to express their views and priorities from the developmental age of 5 years [42]. Families can act as active collaborators to guide the choice of goals that the child needs to achieve in their daily life [43]. However, a scoping review published 2018 highlighted that the role of the parents – and even more so, children – are poorly articulated [14]. Goal formulation can be facilitated by using a validated methodology [44] that considers the child’s wishes [45]. The SMART model (Specific, Measurable, Attractive, Realistic and Time-bound) [46] is a simple model that guides the drafting of goals.

Inter-professional collaboration centered on the child is crucial within each aspect of goal setting to ensure consistency in the actions taken to achieve the goals [11]. Information sharing between the professionals involved in the child’s care is essential for maintaining continuity of care, which is highly valued by patients and their families [47]. Likewise, rehabilitation professionals must facilitate the generation of child and family-driven goals; thus, communication with the patients and their families is essential [48].

In adult rehabilitation, using a clear process facilitates the engagement of individuals in the goal-setting process [49].

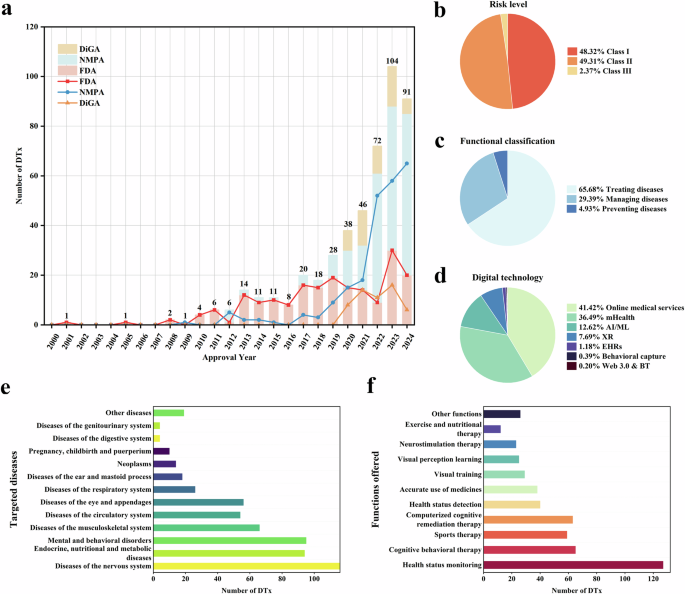

Several articles reported the use of mHealth apps for adolescents, focusing on disease self-management and incorporating self-directed goal setting as a strategy to facilitate the adoption of healthy behaviors [50] or pain coping [51]. However, none involved goal setting in rehabilitation.

Two studies proposed mhealth apps for pediatric rehabilitation professionals to guide at least one part of the goal-setting process, focusing on improving the child’s daily life. The “GOALed app” was developed for pediatric physical therapists to simplify creating, recording, storing, scoring, and interpreting GAS goals. It provides an interface to enter the goal and GAS scores. It enables the visualization of GAS score changes and might facilitate promote greater GAS interpretation. The “Aid for Decision-making in Occupation Choice for School (ADOC-S)” is intended for occupational therapists and aims to assist with conducting collaborative occupation-based goal setting in school. It places particular emphasis on needs identification and prioritization. It provides illustrations of occupations that can be selected by the different stakeholders (child, parent, teacher and occupational therapist) and then prioritized during a discussion facilitated by the occupational therapist.

Ease of use and design are key to facilitating end-user engagement [52] Gamification, a process by which the desirable features of games are used in non-game contexts to leverage a person’s interest in competition might be helpful to promote greater engagement with the technology [52, 53].

Mind map

Specific attention was paid to specifying the roles of each stakeholder (rehabilitation professional, child, parents) in the “Kid’EM-app” with the aim of offering a structured approach to facilitate collaboration. The components of the “Kid’EM tool-paper version” (getting to know the child, identifying and prioritizing needs for goal setting, guidance for formulating goals) were adapted and distributed to the users. In line with the literature review, a collaborative review was held on how to leverage the opportunities offered by digitalization to better involve the child in the process (enhancing their engagement, facilitating collaboration), enable communication with the family and maintain a direct connection with their daily life, and ensure coherent care coordination with other professionals (SM IV).

Development of the application

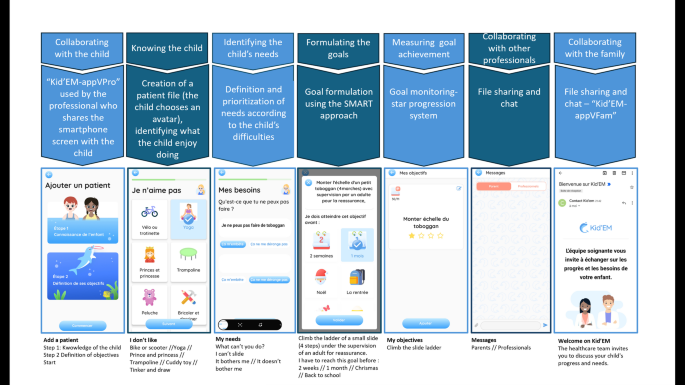

The “Kid’EM-app” prototype has a simple, colorful design, is adapted to children, and is designed to guide and support rehabilitation professionals through the goal-setting process as well as enable them to involve the child and family. We aimed to provide a quick and easy to use tool (requiring only a short time during the session).

To facilitate intra-professional and family communication, the “Kid’EM-app” frontend includes 2 versions: “Kid’EM-appVPro” for rehabilitation professionals to use during sessions with the child, and “Kid’EM-appVFam” for the child’s parents, accessible by invitation from the rehabilitation professional, with a digital space to facilitate exchanges between parents and professionals. The “Kid’EM-app” back office, a user interface built on the back-end to configure the application (e.g., facilitate user management and database modification) without the need for coding, is managed by the research team and allows them to monitor the app.

The “Kid’EM-appVPro” is designed to be used by professionals who share their smartphone screen with the child to place the child at the center of the process. However, the child is never left alone with the tool. It includes the following functions: creating a patient file, identifying what they enjoy, defining and prioritizing needs according to their difficulties, formulating goals, goal monitoring, file sharing, and chat. In the first part, the professional creates a profile for the child, who can choose an avatar. Together, they identify the child’s needs based on what they enjoy, and their difficulties and priorities. In the second part, the professional is guided to formulate SMART goals related to motor rehabilitation. An explanation is provided for each criterion (Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Realistic and Time-bound), and examples of functional objectives are available. The professional completes a free-text box for the first 4 criteria and checks boxes to set the goal over time. This process creates an editable patient file in which progress toward goal achievement can be tracked by the professional and the child with a 4-star system. There is a notes space where the professional can specify barriers and facilitators for the child’s follow-up (e.g., personal and environmental factors). The application also has a chat system for communication between the parents and professionals and between the professionals caring for the child, as well as a feature for sharing the child’s file. (Fig. 1)

The professional can invite colleagues to use the “Kid’EM-appVPro” and parents to use the “Kid’EM-appVFam”. The “Kid’EM-appVFam” enables parents to view the child’s file and access the chat feature allowing the exchange of photos so that the therapist can observe the situations in which the child encounters difficulties in their daily life.

Model of the application functions

After the second sprint, the research team and the steering committee tested the prototype frontend and backend in preproduction. Front-end testing was carried out using download links sent individually by the company to the testers’ email addresses to identify bugs, display issues and text that needed to be changed. Backoffice testing was carried out via a URL provided by the company to the testers to ensure that the parts of the application that allowed customization were working correctly and to check that data were being stored and retrieved correctly from the database.

Phase 2: testing the application prototype

The application prototype was tested by 7 professionals (5 physiotherapists and 2 occupational therapists) (Table 1).

Several testers described the application as “intuitive,” “fun,” and “attractive to the child.” Two of them found it “complicated” to use the “Kid’EM-app” because of bugs.

The functions for creating a patient file, identifying what the child enjoys, defining and prioritizing needs according to their difficulties, formulating goals, and goal monitoring were used by all testers. Two testers asked for help from the research team when using the application for the first time. The sharing the file with family, professionals and chat functions were not used, mainly because it was difficult to access them at this stage of the development. The theoretical use of these functions was underlined by several testers.

The testers reported that the process of identifying what the child enjoys, and defining and prioritizing needs according to their difficulties created a time for exchange with the child and helped establish a relationship. They reported that the guidance provided by the app for the formulation and monitoring of goals helped to systematize child-centered care. The monitoring-goals function provided a simple method to assess the child’s clinical progress. Most felt that there were too few suggestions for identifying what the child enjoys. Some stated that the wording of certain questions was clumsy or too evasive. The testers suggested new functionalities, such as specific versions for different age groups and/or cognitive levels and being able to share summary elements with non-rehabilitation professionals.

The developer resolved bugs when the application was serviced. Existing functionalities were modified according to the feedback from the testers. Items were more positively worded, and the function for identification of what the child enjoys was enriched from the back office. More items with their graphical representation (superheroes, sports activities, creative leisure activities, ….) have been entered in the back office so that they are available to users in the front office. The application was published on download platforms after these changes.

Phase 3: implementation

We recruited 14 professionals to test the application in clinical practice: 7 physiotherapists, 5 occupational therapists and 2 psychomotor therapists, all with a variety of practice modalities (Table 1). They each reported having tested the application with 2 to 10 children, for a total of 53 children. The children who participated had all verbal communication. Their age range was wide (between 7 and 16 years). 52.8% of the children had cerebral palsy, 15.1% orthopaedic diseases, 11.3% neuromuscular diseases, 11.3% neurodevelopmental disorders. Most of the objectives were set in outpatient clinic or rehabilitation centers (Table 2). Most professionals reported having used the “Kid’EM-app” twice for each child during the test (creation of the form and 1 reassessment).

The mean total TAM score was 64.8/100 (SD = 14.6) for all the professions combined (Table 3). The physiotherapists assigned the same score to perceived usefulness and ease of use, whereas the occupational and psychomotor therapists rated perceived ease of use higher than usefulness.

The mean SUS score was 70.9/100 (SD = 10.7), indicating that the testers found the application usable.

In the qualitative analysis, all the testers reported that the “Kid’EM-app” was easy to use and intuitive. Using the app did not substantially increase their workload. They reported a time of 30 to 45 min for the first goal setting – compatible with the use of the tool during a regular rehabilitation session regardless of the practice setting.

The mean satisfaction rating was 5.9/10 (SD = 2.2), with wide variations by profession (mean satisfaction was 6.6 for physiotherapists, 3.5 for psychomotor therapists and 5.8 for occupational therapists) (Table 3).

The qualitative analysis showed that all the testers considered the “Kid’EM-app” to be in line with their practices and values, and it met the need to focus on the child, communicate and exchange with them, and give meaning to their care to keep them motivated. Almost all the testers recommended the app, even though it did not necessarily meet a need they had identified before participating in the study.

Nearly two-thirds of the testers already set rehabilitation goals with children and their families but reported difficulties generating meaningful goals. They found that the SMART approach to goal formulation guided by the application simplified the process. They stated that the “Kid’EM-app” provided a different approach to discussing the reasons for their treatment with the child and to involve the child more effectively in the rehabilitation process. They also found that the app helped to boost communication and motivation during a long-term rehabilitation process. The testers said the children liked the design and were enthusiastic about the medium. However, some testers reported that the graphics seemed too childish for children over the age of 12.

They found that the “Kid’EM-app” needed to provide more guidance on the emergence of needs. Only one tester used the chat function with families. Social (language barriers, etc.) and organizational difficulties frequently complicated communication with families.

The testers questioned the need for an additional communication device when many others exist (email, SMS). A limiting factor in using the “Kid’EM-app” was that it required a smartphone, which was not always allowed in the establishments where the rehabilitation professionals worked. Furthermore, the managers were not always in favor of introducing a new tool.

The professionals suggested several improvements: allowing video-type content to be added, providing assistance with needs identification, enabling hierarchical organization of needs, and widening the range of professionals who could access the application (e.g., special educators and psychologists). (Table 4, SM VI)

link